"Only the dreamer shall understand realities, though in truth his dreaming must be not out of proportion to his waking." - Margaret Fuller

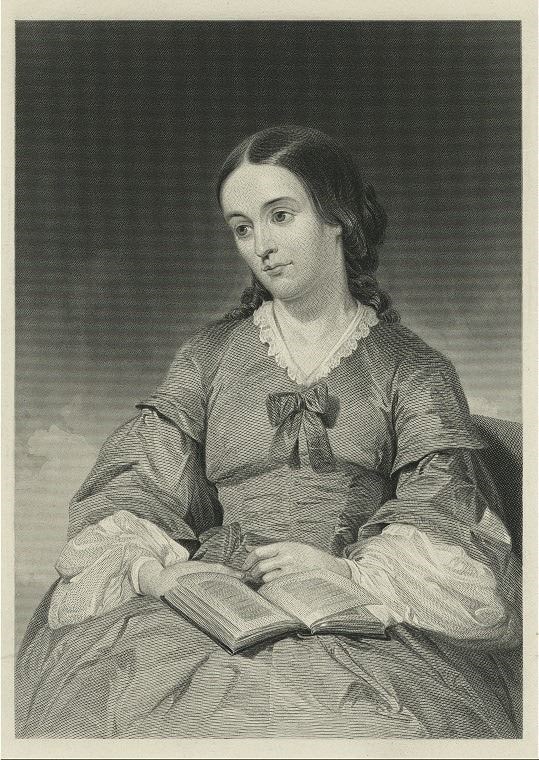

Margaret FullerChappel / Public domainMargaret Fuller Ossoli had more to do with giving the women's rights movement momentum than any other woman during her time, except perhaps First Lady Abigail Adams or Judith Sergant Murray, but both of whom were not only from her father's generation, but were wives and mothers. Fuller was the first female editor of a major literary magazine (The Dial), the first female editor of a major newspaper (The New York Tribune), and invented the role of the literary critic, of which she was the first female. She was also the first female foreign correspondent to Europe, under combat conditions or otherwise. Most importantly, Fuller was key in the development of the women's rights movement, as her publication of her controversial 1844 novel, Woman in the Nineteenth Century, drew attention to the injustices faced by women in society.

Margaret FullerChappel / Public domainMargaret Fuller Ossoli had more to do with giving the women's rights movement momentum than any other woman during her time, except perhaps First Lady Abigail Adams or Judith Sergant Murray, but both of whom were not only from her father's generation, but were wives and mothers. Fuller was the first female editor of a major literary magazine (The Dial), the first female editor of a major newspaper (The New York Tribune), and invented the role of the literary critic, of which she was the first female. She was also the first female foreign correspondent to Europe, under combat conditions or otherwise. Most importantly, Fuller was key in the development of the women's rights movement, as her publication of her controversial 1844 novel, Woman in the Nineteenth Century, drew attention to the injustices faced by women in society.

Margaret Fuller was born Sarah Margaret Fuller to Massachusetts Congressman, Timothy Fuller in 1810. Her father wished for her to be educated, having wanted his first child to be male, and so he granted her the education only allowed to boys. He taught her to read the classics objectively, write coherently, and to study Latin & Greek. Cut off from interaction with girls her own age, Margaret developed habits typically attributed to boys her age. Aside from being gifted with intellect, Margaret had developed a sort of confidence that made it difficult to hide her intelligence, a factor deemed detrimental for young ladies. Although Timothy Fuller tried to remedy his mistake by sending Margaret to an academy for young ladies, the mistake had been made, and his daughter remained steadfast and strong-willed.

Margaret was twenty-five when Timothy Fuller died, in 1835, still living at home, as was customary for young unmarried ladies at that time, on her father's farm. Congressman Fuller left behind a wife and five children, of whom Margaret was the eldest, without any means of visible financial support. The family came to depend on Margaret for financial security, and this meant that Margaret had to work for a living. She took up a job teaching at Bronson Alcott's Temple School, where she left a positive impression, and where she would teach his daughter, a young Louisa May Alcott.

Too talented to be content as a schoolteacher, Margaret began to generate income hosting conversations at the bookstore of Elizabeth Peabody. There, she mesmerized audiences while talking about literature, culture, and mythology, despite societal bans against female speaking in public. Worse, Margaret invited young women to participate in the conversations. In the earliest form of feminist activity, Margaret implored women to speak for themselves without requesting permission from men. She made them feel value in themselves and showed them that they had minds of their own and that their opinions mattered.

As Margaret matured, she would impose her stubborn, iron-willed nature upon the developing Transcendentalist movement, which emphasized equality and appreciation for all forms of life, but was also male dominated. She proved herself more knowledgeable than even the movement's leader, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and was apt at critiquing their works. And, although the male community expressed its jealousy by ostracizing Margaret, she became close friends with Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and Nathaniel Hawthorne. She would be key in establishing the first major literary magazine, The Dial. Margaret Fuller was a driving force in the American realization of its own literary merit. As a critic, she helped to determine what the blossoming country's cultural identity was comprised of. Despite being a fatherless, unmarried woman, she was not afraid to speak her mind and denounce writers she deemed unworthy of recognition, such as James Russell Lowell, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and Edgar Allen Poe.

As Margaret further matured, she distanced herself from the Transcendentalists. She moved to New York City and became affiliated with Horace Greeley's New York Tribune, working as a literary critic and later as an editor. She ventured into the frontier (then the Great Lakes Region consisted of parts of Minnesota and Ohio), where she documented the abuses toward the Native Americans, the harsh living conditions for women in the West, and where she white-water rafted and slept on a billiard table. In her articles, she spoke out against the evils of slavery, expressed disgust at the treatment of prisoners in Sing Sing and Blackwell's Island, and she went so far as to defend prostitutes, whom she interviewed at Sing Sing, citing that they had rights as well. When she returned to New York, she published Woman in the Nineteenth Century, which had originated from an editorial she had written called "The Great Lawsuit." It was the first feminist work of its kind, and was perceived as an abomination to many men in the country, as it was candid in its discussion of matters concerning sexual relations, gender roles, and domestic violence, and was published under the name of a woman, when social law forbade women to publish novels (many respectable women novelists did so under a male pseudonym). Fuller accused men of placing women in a double bind, highlighting their lack of property rights, marriage rights, and voting rights. She claimed that they were seen as moral beacons and were married off to violent men to change their character for the better, but were simultaneously expected to obey their husbands. She accused men of treating women like slaves, which, she explained, was why abolitionists were overwhelmingly women. Most radically, she expressed skepticism at woman's lack of suffrage, and stated that women should have the right to vote in elections. It is believed that this was influential in the organization of the Seneca Falls Convention of 1848, the first organized women's rights conference in the country, or perhaps the world. Fuller, although the work was widely criticized and condemned, became recognized worldwide and a household name.

Fuller's fame and glory was not to last, however. In 1847, Fuller chose to embark on a foreign correspondence mission on behalf of The New York Tribune, across Europe. She heroically took part in the Italian Revolution of 1848, to overthrow Pope Pius IX and to establish a unified Italy, alongside her lover, Count Giovanni Ossoli. She had an illegitimate child with the Count, whom she named Angelino, which sparked a scandal overseas, and cost her job at The Tribune. When the Revolution failed, she and the Count were driven into poverty. Overseas, many rejoiced that a woman who had been so fiercely independent had been reduced to a poor, unmarried mother romanced by an Italian younger than herself. But still, Fuller clung to her Transcendentalist beliefs of equality beneath the eyes of God and refused to perceive her hardship as a "punishment" for her independence. She saw that the only option left for her and her poverty-stricken family was to return to America and attempt to find work. Ralph Waldo Emerson cautioned her not to return, citing the cruelty she would face upon her return, however Margaret was determined to brave the scandal and return to the country she had always loved. She would never make it, however. In 1850, while attempting to return to the country, Fuller and her family were killed in a shipwreck fifty miles off of Fire Island, New York after their boat, The Elizabeth, had struck a sand bar during a rainstorm. Allegedly, Fuller had refused to evacuate the boat without her husband and son.

“Though she gave a strong impetus to the women’s movement, for many New England daughters of later generations Margaret Fuller was held as a dreadful example of the presumptuous woman,” Fuller Biographer Paula Blanchard shrewdly noted. “In her own time, Margaret Fuller became a legendary bogeywoman, symbolizing a threat not only to the male ego but to the family, and thus to the social order." But those Fuller inspired counted. Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony credited her with making them feminists. Louisa May Alcott praised Fuller as one of the great intellectuals, and was likely influenced by her, having known her from childhood. Fuller would inspire the literary community immensely, as one of the first literary critics, she determined the country's artistic direction and self-perception. More interestingly, Nathaniel Hawthorne's Hester Prynne, Louisa May Alcott's Jo March, and Henry James' Isabel Archer, all strong heroines in American literature, are all believed to be based on the independent Margaret Fuller. Fuller is a pillar of heroism in light of her courage and defiance that seemed in vain at the time, but proved to be a catalyst for women in American history. All it seems that our country's women needed to see was what an example of a feminine, confident, self-reliant, and determined young woman looked like.

Page created on 6/15/2010 12:00:00 AM

Last edited 8/15/2020 9:14:42 PM

"'A woman is a nobody,' declared The Public Ledger of Philadephia as late as 1850... 'A wife is everything. A pretty girl is equal to 10,000 men and a mother is, next to God, all powerful. The ladies of Philadelphia therefore...are resolved to maintain their rights as wives, belles, virgins, and mothers and not as women.'" - 1850 article qtd. in The Grimke Sisters from South Carolina (1967) by Gerda Lerner